Society in the aftermath of the First World War

By the end of the First World War, around 17 million servicemen and civilians had lost their lives and overall there had been nearly 40 million casualties, either killed or wounded. Landscapes had been devastated, communities destroyed and individual lives changed forever. Out of the tragedy of the war, however, came new hope - as people returned to peace-time life they brought with them new ideas and attitudes. War-time developments were adopted to civilian use, heralding innovations, inventions and advances in industry and technology, social and political attitudes, housing and medicine. Many of these ideas and attitudes continue to influence our lives today.

New Industry and Technologies

The interwar years are known as the ‘Golden Age of Aviation’. Aviation steadily increased in importance during the First World War and, drawing upon wartime developments, the innovations continued into peace time. Fabric and wood biplanes were replaced by all-metal aircraft. Pioneering trans-Atlantic flights, by Alcock and Brown and later by Lindbergh, opened visions of international travel. Imperial Airways, founded in 1924, developed services to India, South Africa and Australia. Domestic passenger flights also developed. Many of these departed from Croydon, the home of innovations in air traffic control and of the ‘mayday’ emergency call.

Local Link; W.E. Johns, the author of the ‘Biggles’ books, joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 and became an instructor at Marske-by-the-Sea.

Technological developments were not limited to aviation. In 1911, the construction of the first radio listening and tracking station was initiated by the Admiralty. The station, known as a Y station, was located in Stockton-on-Tees and was operational by the start of the war. Coded enemy wireless signals were picked up and forwarded to ‘Room 40’ in Whitehall, where they were decoded. Research on radio techniques and capabilities continued after the war. In 1935 a practical experiment proved that aircraft could be detected by radio waves and ‘radar’ stations were installed along the south and east coasts of England. Radar continues to be used in a variety of applications, including maritime and meteorology.

In 1917, when Billingham was chosen as the site for a new chemical works, it was a small village. The chemical works was developed to make ammonium nitrate, used for explosives and fertilisers. Brunner Mond acquired the government owned works in 1920 and in 1926 Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was formed from the merger of four companies, including Brunner Mond. By the 1930s, the plant was the largest factory in the British Empire and employed over 10,000 people, producing fertilisers, explosive and high octane fuel for aircraft. Billingham expanded to accommodate the plant’s employees. ICI continued to have a major influence on the town until the late 20th century.

Local Link; The author, Aldous Huxley, visited the ICI plant at Billingham during the interwar years. His view of the works, ‘…an ordered universe in the midst of the larger world of planless incoherence’ was the inspiration for his 1931 novel, Brave New World. A character in the novel, Mustapha Mond, Resident World Controller of Western Europe, is probably named after Sir Alfred Mond, the first chairman of ICI.

Changing Attitudes

By the end of the First World War, social and political attitudes were undergoing changes. Tired of conflict, opinions on war and militarism were altering. Growing interest in the development of an organisation for international peace and justice lead to the establishment of the League of Nations by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Among the organisation’s functions were preventing war through disarmament, international justice and health. Whilst the League ultimately failed in its purposes, many of its functions were transferred to the United Nations, established in 1945. Through its various departments and agencies, such as the Security Council, UNICEF and the World Health Organisation, the United Nations continues to benefit people today.

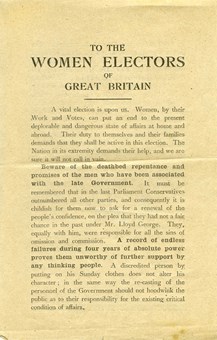

Women’s contribution to the war effort led to a change in perception of their role in society. This led to support for votes for women. In 1918, Parliament passed The Representation of the People Act, giving votes to women aged over 30 who owned or lived in property with a rateable value of £5. The act also gave the vote to men over 21, whether or not they owned property. About 8.4 million women gained the vote. Another act in November 1918 allowed women to stand as MPs and in 1928, women were given the same voting rights as men.

Greater freedoms for women and changing social attitudes post-war were reflected in fashion. Looser fitting dresses, dropped waists and bar shoes allowed women to literally ‘kick up their heels’ to dance the Charleston or tango. Men’s clothing, particularly leisure wear, became more relaxed, influenced in part by Edward, Prince of Wales, and film stars such as Rudolf Valentino. Whilst formality in dress did not disappear, there was a greater emphasis on comfort and practicality, a factor which continues to influence manufacture today.

Credit - Courtesy of Preston Park Museum & Grounds

Local Link; Annie Clephan, who gave an art collection to Preston Park Museum, was an important activist for women’s rights. She was President of the National Union of Women Workers and was also influential in helping women join the police force.

The Role of Women

During the war, women had taken on jobs which had been previously seen as ‘men’s work’. Women worked on the railways and many of the staff at Stockton Station were female. Women were also employed as police, postal workers, bus and tram conductors, in the civil service and in factories and industry. Although at the end of the war many women lost their jobs as they were replaced by men demobbed from the services, by the 1930s about one third of British women over 15 worked outside the home.

Whilst many poorer women had, of necessity, gone out to work before the war, most middle class women had regarded marriage and home-making as their destiny. The death of so many men from one generation meant that there were around 1¾ million ‘surplus women’ after the war. Girls began to consider careers; the Principal of Cheltenham Ladies College noted that whilst pre-war most girls had left school and returned to their families, post war

‘… certainly seventy per cent wished to have a career’. Professional opportunities for single women increased following the Sex Disqualification Act of 1919, opening work in banking, accountancy, engineering and law.

Women were generally paid lower wages than men in the workforce. Women campaigned for more equal pay - in 1918 women workers on London buses went on strike and were ultimately successful in demanding the same increase in pay as men. The Women’s Institute (or WI) formed in 1915 and quickly grew. Non-party political, the WI has a long history of campaigning, with early resolutions calling for ‘convenient and sanitary houses’ and equal pay for women. Recent WI campaigns include food waste, climate change and mental health.

Women Electors leaflet.

Credit: Courtesy of Preston Park Museum & Grounds

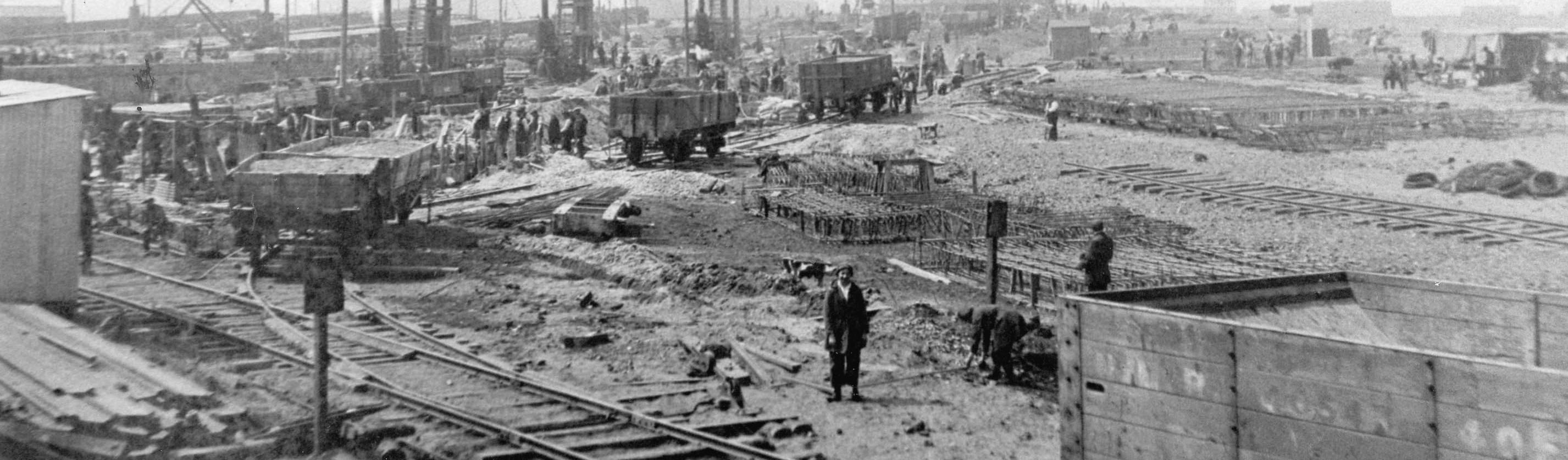

Woman worker, Haverton Hill shipyards, circa 1919.

Credit: Courtesy of Stockton Libraries

Homes Fit For Heroes

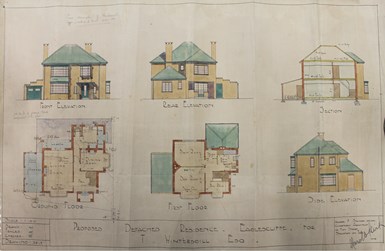

In 1918 the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, made a speech promising ‘habitations fit for the heroes who have won the war’. This aim, reported by the press as ‘Homes Fit For Heroes’, faced several major issues - the lack of funds, the lack of skilled manpower and the lack of materials in the building industry. To tackle the problem of a shortage of materials and skilled builders, innovative design and construction methods were used and different materials deployed. These included concrete but also oddities such as terracotta blocks and short gable ends. Pioneering design features were also used, based on the Tudor Walters report, ensuring new houses had modern baths and bedrooms. Cul-de-sacs were used to reduce road building and further lower costs.

From 1919 the Government had concerns that, due to the Russian revolution, the working classes would be encouraged by radical Bolshevism and rise up if they felt mistreated. Funds were allocated to win over the working classes. The Government worked on new housing reforms and set up social housing and subsidies for local government and private builders. This was to enable house building to accommodate returning soldiers and to assist the movement of workers to factories and industrial areas from the countryside.

In Teesside, the First World War brought a huge need for ships and Furness Shipyard was constructed on marshland in 1918. A million tons of slag and ash were added on the shore, to increase the level of the land to about 4.3 metres. Lord Furness built a hostel for his workers to live in until he had built houses for them. Each house had its own garden and the estate was named Belasis Village, Billingham, but was known as the “garden estate”. There were 531 houses and they were built in 438 days.

Architectural drawings of a detached house in Eaglescliffe, circa 1920

Credit: Courtesy of Preston Park Museum & Grounds

Medical Marvels

Due to the many serious and life-changing injuries suffered during the world-wide conflict of 1914-1918, medicine advanced to help heal and rebuild the lives of those affected. When the war ended, many of these developments were applied to peace time conditions.

The use of poison gases – such as chlorine – as weapons in the First World War killed and disabled soldiers and civilians. Many survivors of gas attacks were left with long-term injuries, such as respiratory diseases and failing eye-sight. Although mustard gas destroyed white blood cells, it lead doctors to realise that it could also kill cancerous cells, beginning the era of chemotherapy.

Shells, machine-gun bullets and shrapnel lead to many amputations and the need for artificial limbs. The Desoutter brothers had created the first aluminium prosthetic after Marcel Desoutter lost his leg in a flying accident. The brothers established a factory in 1914, specialising in the production of lightweight articulated duralumin limbs. Companies, such as J F Rowley and Carnes, introduced other innovations to improve their products to help the casualties of the war.

Trench warfare lead to devastating jaw and facial injuries as the head was the most exposed part of body. Artists and sculptors, such as Francis Derwent Wood, created facial masks of painted galvanised copper to conceal missing noses, chins and cheekbones. Preferring not to cover disfigurements, Harold Gillies, a New Zealand surgeon, worked to reconstruct faces. Focussing on aesthetics, he tried to give patients back the appearance they had pre-injury. Gillies developed procedures and techniques, including the tube pedicle, grafting tissue to the injured area from elsewhere on the body. His cousin, Archibald McIndoe, continued these advances, treating badly burnt pilots, the ‘Guinea Pig Club’, during the Second World War.

Traumatic physical injuries could cause long term emotional issues. Some servicemen suffered psychological injuries however they appeared physically unhurt. This condition was described as ‘shellshock’ (known today as post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD). These patients received a variety of treatments, including ‘talking therapies’ and occupational health activities. Similar treatments continue to help those with mental health problems today.

Carnes Artificial Arm advert.

Credit: Courtesy of Preston Park Museum & Grounds