Most people in the Borough may have heard of the Edmund Harvey Centre, even if they do not know what part of the community it serves. In the November of 1971 Teesside County Borough’s Education Committee put in a planning application for the erection of a Speech Therapy and Child Guidance Centre at Queens Street, Cromwell Avenue, Stockton on Tees, and that’s how it all got started, but who was Edmund Harvey and what connection did he have to children’s education?

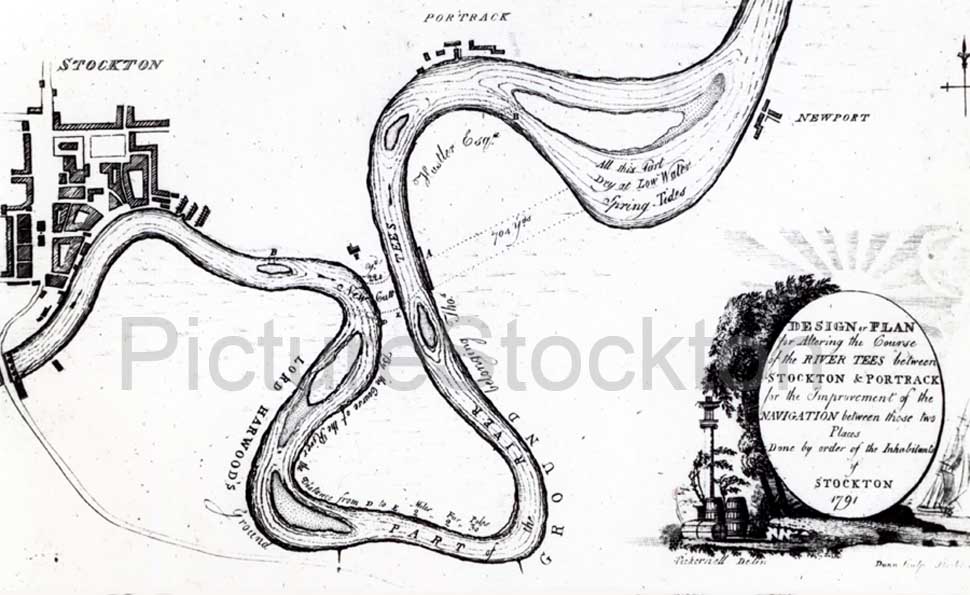

To find the answer you could visit Stockton’s reference library and look through the local history books where you will come across John Brewster’s “Parochial History and Antiquities of Stockton-On-Tees” published in Stockton in 1796, with a second and enlarged edition printed in 1829, which is the one we are interested in. Brewster, Wikipedia tells us, became a curate in Stockton in 1776 followed by a spell from 1777 to 1791 at Greatham before returning to Stockton as the Vicar. He died in Egglescliffe on the 28th of November 1842, aged 89. In a part of his book (which can also be found online, simply by typing in the title) he reserves a section for posthumously famous respectable though obscure tradesmen. One of them being Edmund Harvey, a local Pewterer, who unceasingly, but fruitlessly, pressed for the opening of a cut or channel on the River Tees. His memorial upon this subject was made out of two plates of copper dated 1769 in the exact shape of the curve of the river which he believed should be by-passed, and he pressed the issue until his eventual demise.

At the time when Brewster knew Edmund Harvey he attended the Morning Prayer service at the Parish Church with half a dozen poor boys in tow which he used to educate, using his workshop in Finkle Street as a school room and a Thomas Richmond of Market Place Stockton relates in his “local records of Stockton and the neighbourhood” completed in 1788 (but not published until 1868) that with the assistance of well-disposed persons, also clothed them. Afterwards in about 1769, he added to his school six girls, and, by the further aid of his friends, was enabled to engage a young female to instruct them in needle-work, the resulting income also provided him with a modest pension.

Although not a contemporary of Edmund Harvey, Henry Heaviside in his “Annals of Stockton on Tees” published in 1865 informed us that In order to perpetuate Edmund’s good work after his demise, the trustees of Bishop Crewe were petitioned for assistance (according to their website Lord Crewe's Charity was established in about 1721 under the terms of the will of Nathaniel Lord Crewe, Bishop of Durham, to distribute the income from his estates in the North East of England for the benefit of necessitous clergy and educational purposes in the ancient Diocese of Durham ) since the contributions to Edmund obtained from his funders were not sufficient to provide a lasting foundation to continue his work for future generations, but sadly no one came forward to take on the work. Brewster stated, “He was one of the last instances of the pious and simple manners of departing times.”

Henry Mellanby, who was for a few years a schoolmaster in Rams Wynd AKA Ramsgate Street, and afterwards a clerk in a solicitous office, was one of Mr. Harvey's pupils, and wrote two pieces of poetry on his death; one of them was inserted in the "Newcastle Ladies' Pocket-book" for 1787; the other (given below) was composed the previous year.

“But all our praises have not Lords engross’d,

I’ll tempt my muse to sing the man we’ve lost,

Who, while he liv’d, possess’d a small estate,

So not much meanly poor nor idly great;

And to such pious uses he applied His life and fortune till the day he died,

That all who knew him cannot but confess

He cloth’d the naked-fed the fatherless;

The unlearned instructed; carefully subjoined

Such moral precepts in the tender mind

Of youth, that they pass calmly thro’ the strife

Look back, when to the verge of life the come,

In full assurance of their peaceful doom;

Survey their friends, and bless the happy man

Who first taught them the ways of God to Scan.”

Brewster goes on to state in his parochial history that when he first arrived in Stockton as a curate some fifty years earlier Edmond used to lay little scrapes of paper, with admonitory texts of scripture on the vestry table to attract his attention: which were always well taken as they were well intended. However, he had got hold of a few sheets of copper on which government duty had not been payed and several years later he felt so bad at defrauding the revenue that he resolved to ease his conscience by paying the outstanding duty. He attended the customs-house on several occasions to make the repayment but they refused to receive it, and laughed at his scruples. Eventually he threw the money down in front of them, telling they might give it to the poor and stormed out, stating later on “I consider it my duty to render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God which is God’s”

Almost thirty years after Edmund Harvey’s demise on the 18th of September the cut in the river at Portrack point was opened with a great fanfare following the sound of guns and three sloops, the custom house boat, the Redcar life boat along with numerous pleasure boats sailing through it. The cut shortened the distance from Stockton to the sea by nearly three miles. Prior to it’s opening, vessels bound to Stockton had to sail round by Mandale and Portrack, where they frequently had to wait for days for a fair wind before they could reach the Port. It was only 200 yards, (183 meters) across and cost a total of £12,163s. 4d. the main holdup seems to have been in setting up a stable management company to improve the viability of the Port and to raise the necessary capital to fund the work. A second bigger cut 1,100 yards (1 km) was completed in 1831. Since the meander was shorter and the cut longer the net reduction in distance was less long, but the bypassing of islands and sandbars in the Portrack meander still made it worthwhile.

Edmund Harvey lived and worked for many years at No 9 Finkle Street hammering out his pewter artefacts. In their Booklet “The Buildings of Stockton on Tees” by Robin Daniels of Tees Archaeology we are informed that between 1680 and 1710 there was a major rebuilding of the houses of Stockton using bricks and tiles and quite probably stone salvaged from Stockton Castle (as is supposed to be the case in Finkle Street). The stone built buildings are notable lower than ones constructed at a later date.

Edmund Harvey was christened on the 27th of December 1698 in Stockton and died 1781 aged 83. Over the years he worked his trade producing items made out of pewter which is an amalgam of 85–99% tin, mixed with copper, antimony, bismuth and in early times lead which gave the metal a dark appearance, later on other more acceptable metals were used. In those days, there was scarcely a household in Britain that did not possess some items of pewter. It is a very environmentally sound product, especially when they got rid of the lead amalgam, you can repair it, re-smelt it, and shape into all sorts of useful things such as plates, bowls, candlesticks, and buttons. There is an example of Edmund’s work in Preston Park in the shape of a serving plate acquired on a loan from the Getty Museum, although he is better known today for his pewter work in churches, of which more examples survive possibly because they were not in everyday use. Bonhams the auctioneers had an example of Edmund Harvey work at their Chester sale on 17 January 2017 namely a straight-sided York flagon produced in about 1690 estimating the value at between £4000-6000 suggesting he was something more than a simple pewterest.

There is some surviving pewter work by a Lawrence Harvey born on 23 January 1659 at Wigan, Lancashire who may have been Edmund’s father, and although the dates fit nicely one cannot be sure about it.

There are quite a few assertions going about claiming that he was the first of this and that, which or may not be true. However we prefer to think of him as modest, honest man trying to do his best for his community by providing good basic education to help up lift some of the under privileged children making him an early pioneer of Ragged Schools, and of course his favourite subject, making a cut on the Tees.

Image Source:

Altering the course of the River Tees - 1791; Courtesy of Picture Stockton.

The Story of Edmund Harvey was kindly submitted by Bryan & Vicky Cooper.